Theory Theory: She Doesn't Know What I Think I See (How We Construct Meaning in Art)

- Deodato Salafia

- Mar 9

- 4 min read

Updated: Mar 11

Have you ever found yourself standing in front of a contemporary artwork and thinking, “But what does it mean?” Or, on the contrary, feeling deeply moved by an abstract painting while the person next to you dismisses it with a shrug?

The truth is, we don’t all see the same things. Not because our eyes work differently, but because our brains interpret reality based on mental models we’ve built over time. This is precisely the core of Theory Theory, a concept in perception and knowledge that explains how we understand the world—and therefore art—through inferences and hypotheses.

It’s not a new idea: philosophers and neuroscientists such as Alvin Goldman, Gopnik and Meltzoff, and Daniel Dennett have studied how we form mental theories to make sense of reality. The brain, in essence, is an investigator that gathers clues, formulates hypotheses, and continuously updates its perception of the world.

And this dynamic is fundamental in art.

Seeing Doesn’t Mean Understanding

When we look at a work of art, we don’t just register colors and shapes—our brain immediately starts working to make sense of it. If we see a hyperrealistic painting, the process is simple because we instantly recognize the subject. But if we’re standing in front of a Mark Rothko piece, with its soft fields of color, our mind struggles more: “What does this represent? What is it telling me?”

At this point, our knowledge and sensitivity come into play. If we know that Rothko aimed to evoke deep emotions through color, we are more likely to feel a connection. But if we’ve never heard of him, we might just think, “These are just overlapping rectangles!”

This difference in perception proves that art isn’t just about what we see, but about what we believe we see. Philosopher Alva Noë, in his book Action in Perception (2004), explains that perception isn’t a passive process—it is guided by our interaction with the world. We don’t simply see a work of art; we understand it through our engagement with it.

This means we can’t think of artistic perception as something isolated from experience. Seeing a work of art is a cognitive act, shaped by what we know, our expectations, and even our physical presence. That’s why we can learn to see art differently, and why a piece that once seemed incomprehensible can take on meaning over time.

Context Changes Everything

Then, there’s the factor of context. If you found a urinal in a public restroom, you would never think of calling it a work of art. But the same urinal, signed R. Mutt and exhibited by Marcel Duchamp, became a revolutionary statement in the art world.

How is that possible? Because our brain has a theory about what counts as art and what doesn’t. And that theory shifts depending on the situation. If an object is placed in a museum, we activate a different mental model: “If it’s displayed here, it must have a deeper meaning.”

The same applies to Maurizio Cattelan’s famous banana taped to a wall (Comedian). In a supermarket, it’s just a banana; in a gallery, it sparks debate and redefines the concept of value in art. It’s not the object itself that changes—it’s our interpretation.

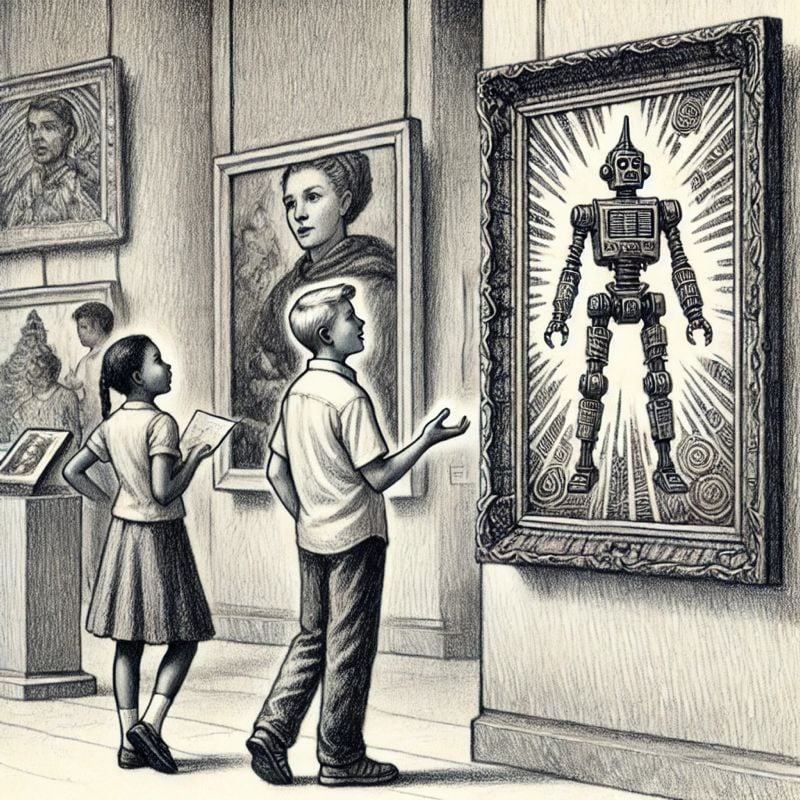

AI-Generated Art Challenges Our Perception

Today, this dynamic is more evident than ever with AI-generated art. If we see a stunning painting and then learn that it was created by an algorithm, our perception shifts. Why? Because our brain operates on the mental theory that art is an expression of human intention. If that intention is missing, can it still be considered art? (Read the article: Can AI Create Art? The Definitive Answer.)

Some would say yes, arguing that aesthetics matter more than authorship. Others would disagree, asserting that art is fundamentally a form of communication—and if there is no human creator behind it, something essential is lost. But ultimately, the point remains the same: it’s not the artwork that changes, but the way we perceive it, shaped by the mental models we carry within us.

Art Is an Experiment on Our Minds

This is why contemporary art is so divisive—it forces us to rethink our mental frameworks. If we are accustomed to the idea that art must depict something recognizable, a conceptual or abstract work may seem incomprehensible. But if we accept that art can be a conceptual, emotional, or social experience, our perspective shifts entirely.

In a way, all art is an experiment on perception. It doesn’t just show us the world—it reveals how we see it. So, the next time you stand before a strange or provocative artwork, instead of asking, “What does it mean?”, try asking yourself, “What is my brain telling me?”

References

Dennett, D. C. (1987). The Intentional Stance. The MIT Press.

Gopnik, A., & Meltzoff, A. N. (1997). Words, Thoughts, and Theories. The MIT Press.

Goldman, A. I. (2006). Simulating Minds: The Philosophy, Psychology, and Neuroscience of Mindreading. Oxford University Press.

Noë, A. (2004). Action in Perception. The MIT Press.

Artworks

Duchamp, M. (1917). Fountain. Ready-made.

Rothko, M. (1950s). Color Field Paintings. Abstract Expressionism.

Cattelan, M. (2019). Comedian. Banana and duct tape, Art Basel Miami.

.png)

Comentarios